Current density and current

Most electrical devices are not electrostatic devices. Most electrical

devices require the flow of a current. A current requires

moving charges.

Let ρ+ = n+q+

be the density of the positive charges in some region, i.e. the amount

of positive charge per unit volume, and let ρ- = n-q-

be the density

of the negative charges. Here n+ and n- are the number of positively and

negatively charged particles per unit volume and q+ and q-

are the charge of each positively and negatively charged particle,

respectively.

(n+ and n- are positive numbers q+ is a

positive number with units and q- is a negative number with

units. Therefore ρ+ is a positive number with units and ρ-

is a negative number with units.)

In neutral ordinary matter ρ+ + ρ-

= 0, i.e. the net charge per unit volume is zero.

The current density is

defined as j = ρ+<v+> + ρ-<v->.

The current density is

defined as j = ρ+<v+> + ρ-<v->.

In this expression <v+> and <v-> are the

average velocities of the positive and negative charges, respectively.

If <v-> = 0 and only positive charges are

moving, then the direction of the current density is the direction of

the velocity of the positive charges. In ordinary conductors the

positive charges have zero average velocity and only the negative

charges are moving. Then the direction of the current density is

opposite to the direction of the velocity of the negative charges, as

shown in the diagram on the right.

The SI unit of current density is (C/m3)(m/s) = C/(m2s).

The current density is a vector. Its magnitude is the net

amount of charge that crosses a unit area perpendicular to its direction

per second in the direction of j minus the net amount of charge

that crosses the same unit area per second opposite to the direction of

j. If just as many negative as positive charges move across

a unit area in the same direction per second, then the current density

is zero.

The electric current

I is the net amount of charge which flows through a surface, i.e. the

flux of the current density

through a surface area.

I = ∫j∙dA = dQ/dt.

If j is uniform across the surface and constant in time, then

I = j∙A = j*Aperpendicular =

ΔQ/Δt.

The SI unit of current is Ampere

= Coulomb/second (A = C/s). The current I is not a

vector. It is a scalar, but it can be a negative or positive

number. When obtaining the current from the current density using

I = j∙A,

we have to choose a direction for the unit vector n normal to the

surface area through which the current flows. If the net flow of positive charge is in the direction of

n, (or the net flow of negative charge is in a

direction opposite to the direction of n), then the

current I is positive. If the reverse is true, then the current I

is negative.

Assume that a

steady current flows in a wire

with cross-sectional area A. The electrons move with constant

average velocity to the left as shown in the diagram. The

current density is a vector pointing towards the right. Let the

normal to the cross-sectional area point towards the right. Then I = j*A = ΔQ/Δt, and the current is a positive number.

(If the electrons were moving towards the right, then j would

point towards the left and I would be a negative number.)

Assume that a

steady current flows in a wire

with cross-sectional area A. The electrons move with constant

average velocity to the left as shown in the diagram. The

current density is a vector pointing towards the right. Let the

normal to the cross-sectional area point towards the right. Then I = j*A = ΔQ/Δt, and the current is a positive number.

(If the electrons were moving towards the right, then j would

point towards the left and I would be a negative number.)

The magnitude of the current I moving through a wire is given by

I = |ρ-|<v->A = n-|q-|<v->A

= -neqe<v->A,

where ne

is the number of free electrons per unit volume. The magnitude of the current I equals the

number of electrons that pass any point along the wire per second times the unit

of charge qe = 1.6*10-19 C. <v-> is the drift speed

of the electrons. It is their average speed, as they move along

the wire.

Currents are most often produced by the movement of electrons in conductors.

But the movement of ions can also produce a current.

External links:

Ionizing air with fire:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PwzoLsAdrRA

MIT Physics Demo -- Conductivity of Ionized Water:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rf2mS4J0FNg

Problem:

In a storm, falling raindrops carry a current density of +1.0*10-5

A/m2 towards the ground. If 1000 drops strike each square meter

of ground per second, calculate the magnitude and sign of the average charge on

each raindrop in Coulomb.

Solution:

- Reasoning

The the current density is given. j = +1.0*10-5 A/m2 =

+1.0*10-5 C/(s m2), downward.

1000 drops per square meter carrying positive charge produce this current

density.

- Details of the calculation:

1.0*10-5 C/(s m2) = 1000 drops/(s m2) *

Q C/drop

Q = 10-8 C is the average charge on each raindrop.

What causes the electrons to move in a wire?

Particles accelerate when they acted on by

forces. When a particle with charge q is placed in an electric

field E, a force F = qE is

acting on the particle and it accelerates. To produce an electric field,

something has to do work and separate charges. Such a device is

called an emf.

Examples of an emf are a battery or a power supply. Such an emf

separates charges by moving electrons internally from its positive to

its negative terminal. This produces an electric field, which

points from the positive to the negative terminal outside and inside the

emf. Electrons in a wire placed in this electric field close to

the battery will accelerate toward the end of the wire closest to the

positive terminal. But if the wire is not connected to the

terminals of the emf, they will pile up at one end of the wire, leaving

net positive charge at the other end. The separated charges in the

wire then produce their own electric field opposing the field produced

by the emf. The interior of the wire will be field free and

charges will no longer accelerate.

Particles accelerate when they acted on by

forces. When a particle with charge q is placed in an electric

field E, a force F = qE is

acting on the particle and it accelerates. To produce an electric field,

something has to do work and separate charges. Such a device is

called an emf.

Examples of an emf are a battery or a power supply. Such an emf

separates charges by moving electrons internally from its positive to

its negative terminal. This produces an electric field, which

points from the positive to the negative terminal outside and inside the

emf. Electrons in a wire placed in this electric field close to

the battery will accelerate toward the end of the wire closest to the

positive terminal. But if the wire is not connected to the

terminals of the emf, they will pile up at one end of the wire, leaving

net positive charge at the other end. The separated charges in the

wire then produce their own electric field opposing the field produced

by the emf. The interior of the wire will be field free and

charges will no longer accelerate.

If, however, the wire is

connected to the emf, then the emf can pump the electrons through its

interior back from the positive to the negative terminal. Then

field inside the wire will not be zero, and electrons will continue to

accelerate towards the positive terminal.

If, however, the wire is

connected to the emf, then the emf can pump the electrons through its

interior back from the positive to the negative terminal. Then

field inside the wire will not be zero, and electrons will continue to

accelerate towards the positive terminal.

Steady currents can only flow in

continuous loops. At any point, just as much charge has to

flow out of a small volume surrounding the point as flows into the

volume. If this were not so, charge would accumulate at the point,

setting up its own electric field. This field would exert an

additional force on the moving charges, disrupting the steady current.

The electric field in a homogeneous wire with constant cross-sectional

area carrying a steady current is the same everywhere. If it were

not, electrons would move with different velocities in different

sections, and charges would accumulate in certain regions. The

field produced by these charges would disrupt the steady current.

The diagram on the right shows the field in a wire carrying a steady

current.

Even though an electric force is continuously acting on each electrons in a

wire when a steady current is flowing, the electrons do not continue to

accelerate indefinitely, but reach an average terminal velocity, called the

drift velocity <v->.

When the electrons move with the drift velocity, then the resistive forces

(frictional forces) acting on them are equal in magnitude and opposite in

direction to the electric forces. Typical drift speeds are on the order of

1 mm/s.

The resistive forces depend on the type of material the wire is made of.

The terminal velocity depends on the electric force and the resistive force.

The higher the terminal velocity, the larger is the current. The current

will increase if the voltage across the wire increases, (this increases the

strength of the electric field), and decrease if the resistive forces increase

in strength. We write

The resistive forces depend on the type of material the wire is made of.

The terminal velocity depends on the electric force and the resistive force.

The higher the terminal velocity, the larger is the current. The current

will increase if the voltage across the wire increases, (this increases the

strength of the electric field), and decrease if the resistive forces increase

in strength. We write

I = ΔV/R, or R = ΔV/I.

This expression defines the resistance R

of the wire. The resistance is a measure of the resistive forces. The unit

of resistance is

Ohm = Volt/Ampere (Ω = V/A).

Summary:

-

Steady currents flow in continuous loops.

-

The emf does work separating charges and supplies voltage.

It raises the potential energy of the charges

This potential energy is converted to other forms of energy as charges move through the circuit and recombine, only to be separated again by the emf.

-

In resistors, the potential energy is converted into

thermal energy.

Problem:

An emf source of 6.0 V is connected to a purely resistive lamp and a current

of 2.0 A flows. All the wires are resistance-free. What is the

resistance of the lamp?

Solution:

- Reasoning:

The resistance is defined as the ratio ΔV/I.

- Details of the calculation:

R = ΔV/I = (6 V)/(2 A) = 3 Ω.

The resistivity ρ of a material is the

resistance of a piece of material with unit cross sectional area and unit

length. The resistance of a wire is proportional to its length l

and inverse proportional to its cross-sectional area A. We have

R = ρl/A.

The unit of resistivity is

Ωm. The conductivity

σ of a material is σ = 1/ρ.

External link:

Resistivity and Temperature Coefficient at 20o C of common materials

The resistivity is a property of the material a conductor is made of.

For many conductors it only weakly depends on the voltage ΔV across the

conductor or the current I flowing through the conductor over a wide range of

voltages and currents as long as the temperature of the material is held

constant. This is called Ohm's law.

R = ΔV/I is approximately constant for many conductors at constant temperature.

Ohm's law breaks down under extreme conditions for all

conductors. Many modern materials do not obey Ohms law under

any circumstances. (Such materials are called non-ohmic materials.)

The resistivity and therefore the resistance of most materials depends on the

temperature. Tables often list the resistivity at some reference

temperature T0, (for example at 20oC), and then list a

temperature coefficient α = (1/ρ0)Δρ/ΔT. To find the resistance

at some temperature T use ρ = ρ0[1 +α (T - T0)].

A thermistors is a semiconductor crystal whose resistance strongly depends on

temperature. Thermistor thermometers use thermistors to measure

temperature. The resistance is measured to obtain the temperature.

Thermistors are used as clinical temperature sensors in stethoscopes, as probes

during surgery, and in other medical devices where temperature detection and

control is vital.

Problem:

A annealed copper wire has a length of 160 m and a diameter of 1.00 mm. If the

wire is connected to a 1.5 V battery, how much current flows through the wire?

Solution:

- Reasoning:

The current can be found from Ohm's Law, V = IR. V is

the battery voltage, so if R can be determined, the current can be

calculated.

The resistance of the wire is R = ρl/A.

For

copper ρ = 1.72*10-8 Ωm.

- Details of the calculation:

The cross-sectional area of the wire

is A = πr2 = π(0.0005)2 = 7.85*0-7

m2.

The resistance of the wire then is ((1.72*10-8)*160/(7.85*10-7))Ω

= 3.5 Ω.

The current is I = V/R = (1.5/3.5)A = 0.428 A.

Problem:

An aluminum wire has a resistance of 0.10 Ω. If you draw this wire

through a die, making it thinner and twice as long, what will be its new

resistance?

Solution:

- Reasoning:

The initial resistance Ri of the aluminum wire

with length L and cross-sectional area A is equal to is Ri = ρl/A.

The initial volume of the wire is AL. After passing the wire through the

die, its length has changed to L' and its cross-sectional area is equal A'.

Its final volume is therefore equal to A'L'. Since the density of the

aluminum does not change, the volume of the wire does not change, and

therefore the initial and final dimensions of the wire are related by AL =

A'L'.

- Details of the calculation:

We have A' = L/L'A = A/2.

The final resistance Rf of

the wire is given by Rf = ρL'/A' = 4ρL/A = 4Ri

= 0.40 Ω.

Problem

A high voltage transmission line has an aluminum cable of diameter 3.0 cm, 200 km long.

What is the resistance of this cable?

Solution:

- Reasoning:

The resistivity of aluminum is 2.65*10-8 Ωm.

The length of the cable is 2*105 m.

The diameter of the cable is 3 cm and its cross-sectional area is equal to

π(d/2)2 or 7.1*10-4

m2. Substituting these values into R =

ρL/A the

resistance of the cable can be determined.

- Details of the calculation:

R = (2.65*10-8*2*105) Ω/( 7.1*10-4)

= 7.5 Ω.

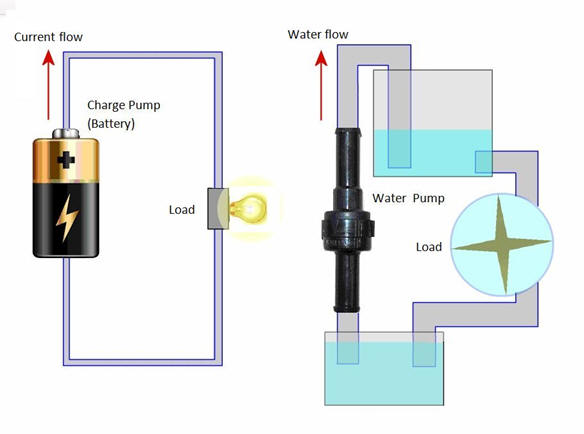

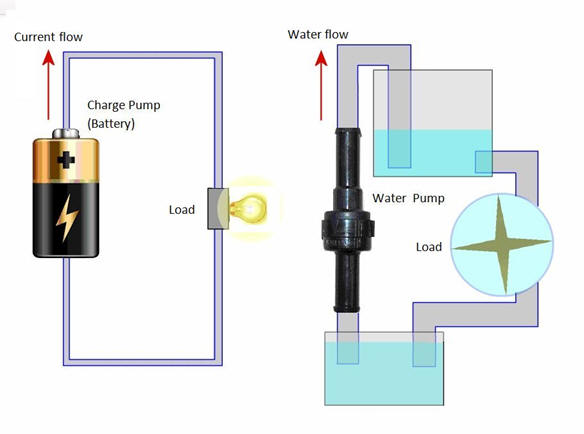

Popular analogy

What is different?

http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/electric/watcir.html

Embedded Question 1

Which diagram below does not represent an electrical current?

Discuss this with your fellow students in the discussion forum!

Discuss different ways one can produce a steady current.

The current density is

defined as j = ρ+<v+> + ρ-<v->.

The current density is

defined as j = ρ+<v+> + ρ-<v->.

Assume that a

steady current flows in a wire

with cross-sectional area A. The electrons move with constant

average velocity to the left as shown in the diagram. The

current density is a vector pointing towards the right. Let the

normal to the cross-sectional area point towards the right. Then I = j*A = ΔQ/Δt, and the current is a positive number.

(If the electrons were moving towards the right, then j would

point towards the left and I would be a negative number.)

Assume that a

steady current flows in a wire

with cross-sectional area A. The electrons move with constant

average velocity to the left as shown in the diagram. The

current density is a vector pointing towards the right. Let the

normal to the cross-sectional area point towards the right. Then I = j*A = ΔQ/Δt, and the current is a positive number.

(If the electrons were moving towards the right, then j would

point towards the left and I would be a negative number.) Particles accelerate when they acted on by

forces. When a particle with charge q is placed in an electric

field E, a force F = qE is

acting on the particle and it accelerates. To produce an electric field,

something has to do work and separate charges. Such a device is

called an emf.

Examples of an emf are a battery or a power supply. Such an emf

separates charges by moving electrons internally from its positive to

its negative terminal. This produces an electric field, which

points from the positive to the negative terminal outside and inside the

emf. Electrons in a wire placed in this electric field close to

the battery will accelerate toward the end of the wire closest to the

positive terminal. But if the wire is not connected to the

terminals of the emf, they will pile up at one end of the wire, leaving

net positive charge at the other end. The separated charges in the

wire then produce their own electric field opposing the field produced

by the emf. The interior of the wire will be field free and

charges will no longer accelerate.

Particles accelerate when they acted on by

forces. When a particle with charge q is placed in an electric

field E, a force F = qE is

acting on the particle and it accelerates. To produce an electric field,

something has to do work and separate charges. Such a device is

called an emf.

Examples of an emf are a battery or a power supply. Such an emf

separates charges by moving electrons internally from its positive to

its negative terminal. This produces an electric field, which

points from the positive to the negative terminal outside and inside the

emf. Electrons in a wire placed in this electric field close to

the battery will accelerate toward the end of the wire closest to the

positive terminal. But if the wire is not connected to the

terminals of the emf, they will pile up at one end of the wire, leaving

net positive charge at the other end. The separated charges in the

wire then produce their own electric field opposing the field produced

by the emf. The interior of the wire will be field free and

charges will no longer accelerate. If, however, the wire is

connected to the emf, then the emf can pump the electrons through its

interior back from the positive to the negative terminal. Then

field inside the wire will not be zero, and electrons will continue to

accelerate towards the positive terminal.

If, however, the wire is

connected to the emf, then the emf can pump the electrons through its

interior back from the positive to the negative terminal. Then

field inside the wire will not be zero, and electrons will continue to

accelerate towards the positive terminal. The resistive forces depend on the type of material the wire is made of.

The terminal velocity depends on the electric force and the resistive force.

The higher the terminal velocity, the larger is the current. The current

will increase if the voltage across the wire increases, (this increases the

strength of the electric field), and decrease if the resistive forces increase

in strength. We write

The resistive forces depend on the type of material the wire is made of.

The terminal velocity depends on the electric force and the resistive force.

The higher the terminal velocity, the larger is the current. The current

will increase if the voltage across the wire increases, (this increases the

strength of the electric field), and decrease if the resistive forces increase

in strength. We write