One end of a spring is attached to a rigid support.

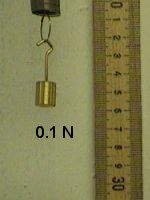

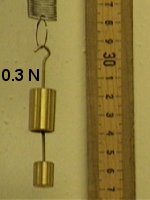

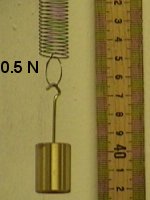

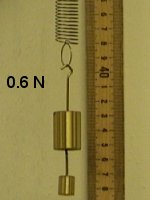

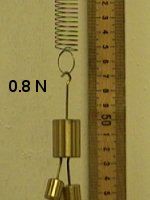

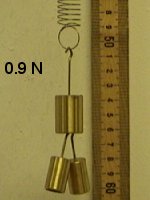

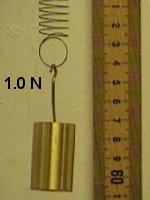

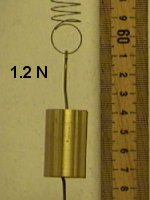

One end of a spring is attached to a rigid support.Different weights are hung on the other end, and the spring stretches to different lengths.

Energy conservation for an isolated system is a fundamental principle of

physics. Energy for an isolated system is always conserved. It may change

forms, but the total amount of energy in an isolated system is constant.

Energy can, however, be converted from one form to another form. Work is the conversion of one form of energy into another.

Energy comes in different forms, kinetic energy, potential energy, chemical

energy, thermal energy, etc. If an object has energy, it has the potential

to do work.

There are several forms of potential energy. Kinetic and potential energy

are called mechanical energy or

ordered energy.

Thermal energy is disordered energy. Friction converts mechanical

energy into disordered energy. When no disordered energy is produced, then

mechanical energy is conserved.

Today we will track the mechanical energy in various systems and explore the relationship between work and energy.

Open a Microsoft Word document to keep a live journal of your experimental procedures and your results. Include all deliverables, (data, graphs, analysis, outcome). Write a 'mini-reflection' immediately after finishing each investigation, experiment or activity, while the logic is fresh in your mind.

Exploration

Use an on-line simulation from the University of Colorado PhET

group to track mechanical energy in a skate park.

Link to the simulation:

https://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulations/energy-skate-park-basics

(a) Click the Playground image. Explore the interface!

Note:

(b) Design your own frictionless track. You can ask for some design guidelines in the discussion forum.

(c) Add friction to your track.

Exploration Deliverables: (to be included in the your journal)

Analysis: What makes a successful track in terms of conservation of mechanical energy? Refer to your conversation with the AI and Charts or Graphs to explain your reasoning.

Outcome: A picture of a successful track with a loop that you have designed.

One end of a spring is attached to a rigid support.

One end of a spring is attached to a rigid support.

Different weights are hung on the other end, and the spring stretches to

different lengths.

Procedure:

| position (m) | force (N) |

| 0.22 | 0.1 |

| 0.255 | 0.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Add two columns to your spreadsheet. For each position, enter the elastic potential energy stored in the spring, ½k(x - xequ)2, and the work done by gravity, mg(x - xequ) = F(x - xequ).

| position (m) | force (N) | ½k(x - xequ)2 (J) | mg(x - xequ) (J) |

| 0.22 | 0.1 | ||

| 0.255 | 0.2 |

Gravity does work, converting gravitational potential energy into other forms.

Experiment 1 Deliverables: (to be included in the your journal)

Visuals: Data table and labeled plots of force versus position (Excel or Python, including trendline) and elastic potential energy stored in the spring versus position (Excel).

Analysis: For masses hanging from a spring in equilibrium you have plots of force versus position of the free end, and elastic potential energy stored in the spring versus position of the free end. What can you learn from these plots?

Outcome: The values (with units) of the spring constant and the equilibrium position.

Convert your log into a lab report.

Name:

E-mail address:

Laboratory 4 Report

Save your Word document (your name_lab4.docx), go to Canvas, Assignments, Lab 4, and submit your document.