Position and displacement

Many of the objects we encounter in everyday life are in motion or have parts

that are in motion. Motion is the rule, not the exception. The physical laws that govern the motion of these objects

are universal, i.e. all the objects move according to the same rules,

and one of the goals of this class is to understand these rules.

When an object moves, its position

changes as a function of time.

The position of an object is

given relative to some agreed upon reference point. It is not enough to just

specify the distance from the

reference point. We also have to specify the direction. Distance is a

scalar quantity, it is a number given in some units. Position is a

vector quantity. It has a magnitude as well

as a direction. The magnitude of a vector quantity is a number (with units)

telling you how much of the quantity there is and the direction tells you which

way it is pointing. A unit vector is a direction

indicator. It is a dimensionless vector with magnitude 1, used to specify

a direction. In text, vector quantities are usually printed in boldface

type or with an arrow above the symbol. Thus, while d = distance, d

= displacement.

External links:

Scalars and Vectors (Please explore!)

Vector Direction

Position

A convenient way to specify the position of an object

is with the help of a coordinate system.

We choose a fixed point, called the origin

and three directed lines, which pass through the origin and are

perpendicular to each other. These lines are called the coordinate axes

of a three-dimensional rectangular (Cartesian) coordinate system and are labeled

the x-, y-, and z-axis. Three numbers with units specify the position of a

point P. These numbers are the x-, y-, and z-coordinates of the point P.

The coordinates of the point P in the

diagram to the right are (a, b, c).

A convenient way to specify the position of an object

is with the help of a coordinate system.

We choose a fixed point, called the origin

and three directed lines, which pass through the origin and are

perpendicular to each other. These lines are called the coordinate axes

of a three-dimensional rectangular (Cartesian) coordinate system and are labeled

the x-, y-, and z-axis. Three numbers with units specify the position of a

point P. These numbers are the x-, y-, and z-coordinates of the point P.

The coordinates of the point P in the

diagram to the right are (a, b, c).

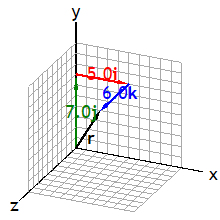

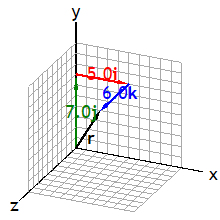

The coordinates of the point P

are the components of the position vector. A unit vector

pointing in the x-direction has a x-component of 1 and y- and z- components of

zero. It is denoted by i. Similarly, a unit vector

pointing in the y-direction is denoted by j, and a unit vector

pointing in the z-direction is denoted by k. Unit vectors

are direction indicators.

The components of any vector add up to form the

vector itself. The position vector of a point P with coordinates (a, b, c)

may be written in terms of its components as

r = ai + bj +

ck.

The magnitude of the position vector is its length r. It

depends on the choice of the origin of the coordinate system. It

is the straight-line distance of P from the origin.

Below is a 3D representation of a position vector

r = ai + bj +ck.

Please click on the image!

To get the best view, change the viewport by dragging the mouse and

zoom in or out as needed.

Click the buttons to choose a different vector

or a different scheme for adding the component vectors.

Example:

Position vector of the Nielsen Physics Building on a small map with the lower left corner as the origin.

AI Study Tip:

Example prompt: 'I am standing at a position of 5 meters. Explain

why this statement is physically incomplete. Act as a tutor and ask me

three questions to help me define my position correctly using the concepts of

origin, coordinate axes, and units.'

Displacement

A change in position is called a displacement. The diagram below shows the

positions P1 and P2 of a player at two different times.

The arrow pointing from P1 to P2 is the

displacement vector.

Its magnitude is the straight-line

distance between P1 and P2.

The components of the displacement vector from P1 to

P2 are (x2 - x1) along the x-axis, (y2

-

y1) along the y-axis.

The displacement vector d from P1 to P2 may

be written as d = (x2 - x1)i + (y2

- y1)j.

The displacement d is (x2 - x1) units in the

x-direction plus (y2 - y1) units in the y-direction.

The magnitude of the displacement is d = ((x2

- x1)2 + (y2 - y1)2)½. This follows from the

Pythagorean

theorem.

In three dimensions the distance between two points P1 with coordinates (x1, y1,

z1) and P2 with coordinates (x2, y2, z2) is

d = ((x2

- x1)2 + (y2 - y1)2

+ (z2 - z1)2)½.

- The distance d is the magnitude of the displacement vector d.

- The

direction of the displacement vector d is the directed line segment from the P1

to P2.

- We call this directed line segment a geometrical or graphical

representation of the vector d.

- We draw an arrow head at P2 to indicate

that the line segment starts at the P1 and ends at P2.

The triple of real numbers dx = (x2 - x1), dy

= (y2 - y1), dz = (z2 - z1)

are called the Cartesian components of d.

External link:

Distance and Displacement (Please explore!)

Remember: Displacement is a vector, distance is a scalar.

Problem:

A football quarterback runs 15.0 m

straight down the playing field (in the

positive x direction) in 2.50 s.

He is then hit and pushed 3.00 m

straight backward in 1.75 s. He

breaks the tackle and runs straight

forward another 21.0 m in 5.20 s.

Calculate his displacement vector and

the total distance traveled.

Solution:

- Reasoning:

Choose a coordinate system so you can track the player.

- Details of the calculation:

Choose your coordinate system so the

player starts at x = 0. After

2.5 s, he ends up at x = 15 m.

He then moves backward 3 m, and ends

up at x = 12 m after another 1.75 s.

He moves forward 21 m in the next

5.2 s and ends up at x = 12 m + 21 m

= 33 m.

His displacement

vector is d = (33 m)i,

i.e. 33 m forward.

His total distance traveled is 15 m

+ 3 m + 21 m = 39 m.

Note: The total distance traveled is NOT the straight-line distance from the

start to the end point if an object does not move in a straight line without

changing direction.

Problem:

While traveling along a straight interstate highway you

notice that the mile marker reads 260. You travel until you reach the 150-mile

marker, and then retrace your path to the 175-mile marker. What is the

magnitude of your resultant displacement from the 260-mile marker?

Solution:

- Reasoning:

The resultant displacement is the vector d, the sum of two vectors

d1

and d2 which point in opposite directions.

- Details of the calculation:

Thee sum of the two displacement vectors is d = d1

+ d1 = (-110 m) + 25 m = -85 m.

You can also argue in the following way.

For the total displacement it only matters where you start and where you

stop.

d = position 2 - position 1 = 175 m - 260 m = -85 m.

Problem:

The tip of a helicopter blade is

5.00 m from the center of rotation.

For one revolution of the blade,

calculate the displacement vector and

the total distance traveled for the tip

of the blade.

Solution:

- Reasoning:

After one revolution, the tip

returns to is original position.

Its displacement vector d =

0.

- Details of the calculation:

The total distance traveled

by the tip equals the circumference

of a circle of radius r = 5 m.

Circumference = 2πr = 31.42 m.

The total distance traveled by the

tip is 31.42 m.

AI Study Tip:

Example prompt: 'I walk 10 m East, 5 m North, and then 10 m West and 5 m

South. Calculate my total distance and my total displacement.

Explain the result to me as if I were a middle school student, focusing on why

one is zero and the other is not. Provide a biological example, such as a

honeybee foraging for pollen, to illustrate these two concepts.'

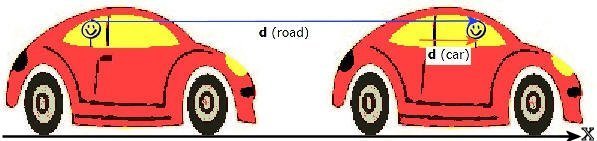

The displacement vector has the same magnitude and direction, independent of the

choice of origin of the coordinate system. The magnitude and direction of the

displacement vector, however, depend on the reference frame in which the

coordinate system is anchored and at rest.

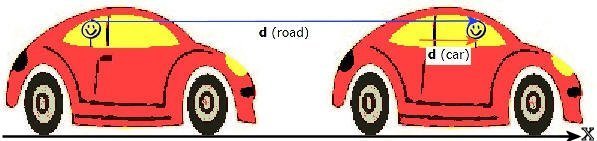

Example:

A car has moved forward a

distance of 6 m, while a child has moved forward from the back seat to the front

seat a distance of 1 m.

- Using the car as a reference frame and anchoring the coordinate system

in the car, the displacement of the child is d (car) = (1 m)i.

- Using the road as a reference frame and anchoring the coordinate system

on the road, the displacement of the child is d (road) = (6 m)i + (1 m)i = (7 m)i.

A convenient way to specify the position of an object

is with the help of a coordinate system.

We choose a fixed point, called the origin

and three directed lines, which pass through the origin and are

perpendicular to each other. These lines are called the coordinate axes

of a three-dimensional rectangular (Cartesian) coordinate system and are labeled

the x-, y-, and z-axis. Three numbers with units specify the position of a

point P. These numbers are the x-, y-, and z-coordinates of the point P.

The coordinates of the point P in the

diagram to the right are (a, b, c).

A convenient way to specify the position of an object

is with the help of a coordinate system.

We choose a fixed point, called the origin

and three directed lines, which pass through the origin and are

perpendicular to each other. These lines are called the coordinate axes

of a three-dimensional rectangular (Cartesian) coordinate system and are labeled

the x-, y-, and z-axis. Three numbers with units specify the position of a

point P. These numbers are the x-, y-, and z-coordinates of the point P.

The coordinates of the point P in the

diagram to the right are (a, b, c).