There is another way to make sure two interfering waves have the same

polarization. We reflect the wave from the two surfaces of a thin film.

This is called division of amplitude.

There is another way to make sure two interfering waves have the same

polarization. We reflect the wave from the two surfaces of a thin film.

This is called division of amplitude. There is another way to make sure two interfering waves have the same

polarization. We reflect the wave from the two surfaces of a thin film.

This is called division of amplitude.

There is another way to make sure two interfering waves have the same

polarization. We reflect the wave from the two surfaces of a thin film.

This is called division of amplitude.

When the medium through which a wave travels abruptly

changes, the wave may be partially or totally reflected. When studying

mechanical waves

we found that when a wave pulse traveling along a

rope reaches the end of the rope, it is totally reflected. The

details of the reflection depend on if the end of the rope is tied down and fixed, or if it is allowed to swing loose.

When the medium through which a wave travels abruptly

changes, the wave may be partially or totally reflected. When studying

mechanical waves

we found that when a wave pulse traveling along a

rope reaches the end of the rope, it is totally reflected. The

details of the reflection depend on if the end of the rope is tied down and fixed, or if it is allowed to swing loose.

A wave pulse, which is totally reflected from a rope with a fixed end is inverted upon

reflection. The phase shift of the reflected wave with respect to the

incident wave is π or 180o.

A wave pulse, which is totally reflected from a rope

with a loose end is not inverted upon reflection. The phase shift of the reflected wave with respect to the incident wave is zero. When a

periodic wave is totally reflected, then the incident wave and the reflected wave travel in the same medium in opposite directions and interfere.

A wave pulse, which is totally reflected from a rope

with a loose end is not inverted upon reflection. The phase shift of the reflected wave with respect to the incident wave is zero. When a

periodic wave is totally reflected, then the incident wave and the reflected wave travel in the same medium in opposite directions and interfere.

We observe a similar phenomenon with light waves.

When a light wave reflects from a medium with a larger index of

refraction, then the phase shift of the reflected wave with respect to

the incident wave is π or 180o.

When a light wave reflects from a medium with a smaller index

of refraction, then the phase shift of the reflected wave with respect

to the incident wave is zero.

We observe a similar phenomenon with light waves.

When a light wave reflects from a medium with a larger index of

refraction, then the phase shift of the reflected wave with respect to

the incident wave is π or 180o.

When a light wave reflects from a medium with a smaller index

of refraction, then the phase shift of the reflected wave with respect

to the incident wave is zero.

Thin-film interference

is the interference of light waves reflecting off the top surface of a thin

film with the waves reflecting from the bottom surface. Constructive and destructive interference

of reflected light waves causes the colorful patterns we often observe

in thin films, such as soap bubbles and layers of oil on water. If the thickness of

the film is on the order of the wavelength of light, then colorful

patterns can be obtained, as shown in the image on the right.

Consider the case of a thin film of oil of thickness t

floating on water. For simplicity, assume that the light is

incident normally, so that the angle of incidence and the angle of

reflection are zero

Consider the case of a thin film of oil of thickness t

floating on water. For simplicity, assume that the light is

incident normally, so that the angle of incidence and the angle of

reflection are zero

In the air, the light reflecting off the air-oil

interface will have a 180o phase shift with respect to the incident

light. A 180o phase shift is equivalent to the light

having traveled a distance of ½ wavelength. In the oil, the

light reflecting from the oil-water interface will have no phase shift

with respect to the light incident on the interface. For the light

reflected off the oil and the light reflected off the water to

constructively interfere we need the two reflected waves to have a phase

shift of an integer multiple of 2π or 360o.

If the light reflected off the oil-water interface travels an additional

distance equal to ½ the wavelength of the light in oil, then the total

phase shift with respect to the light reflected off the air-oil

interface will be 2π.

This happens if the thickness t of the film is equal to 1/4 the wavelength

of the light in oil, since the light has to traverse this thickness

twice. We also get constructive interference if the thickness of the

film is equal to 3/4, 5/4, ..., the wavelength of the light in oil.

For constructive interference we need

2t = (m+½)λn, m = 0,1,2,...,

where λn is the wavelength of the light in oil.

In vacuum we have λf = c. In a medium with index of refraction n we have λnf = c/n. The frequency of oscillation is the same

in vacuum and in a medium, therefore

λn= λ/n.

For constructive interference we therefore need

2 noil t = (m+½)λ, m = 0,1,2,....

Destructive interference occurs when the thickness of the oil film is equal

to (½)λn, λn, (3/2)λn, etc.

For destructive interference we therefore need

2 noil t = mλ, m = 0,1,2,....

If the thickness of the film is (1/4)λn = (1/4)λ/noil the phase of the wave reflected off the top surface is shifted by π by the reflection. The phase of the wave traveling through the film is not shifted by reflection off the bottom surface, but the wave travels an extra distance of λn/2. It will therefore be in phase with the wave reflected off the top surface. If, on the other hand, the film thickness is ½λn, = ½λ/noil then the wave traveling through the film travels an extra distance of one wavelength. It will therefore be out of phase with the wave reflected off the top surface and the two waves will cancel each other out.

Waves incident at an angle θi on the air oil interface are refracted as they enter the oil. fI they are reflected off the second interface, then they are refracted again as they emerge from the oil into the air and then propagate parallel to the waves reflected directly at the air-oil interface. Since the total optical path length difference depends on the wavelength, constructive and destructive interference occur at different angles for different wavelength. The observer sees colored bands.

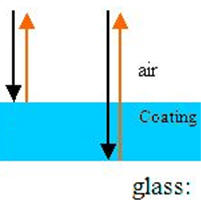

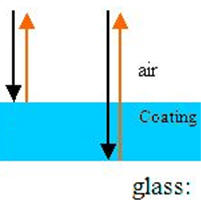

Destructive interference of reflected light waves is utilized to make

non-reflective coatings for light at near normal incidence. Such

coatings are commonly found on camera lenses and binocular lenses, and often

have a bluish tint. The coating is put over glass, and the coating material

generally has an index of refraction less than that of glass.

Then the phase

shift of both reflected waves is 180o.

For such a coating on glass, at normal incidence, we need for constructive

interference

Destructive interference of reflected light waves is utilized to make

non-reflective coatings for light at near normal incidence. Such

coatings are commonly found on camera lenses and binocular lenses, and often

have a bluish tint. The coating is put over glass, and the coating material

generally has an index of refraction less than that of glass.

Then the phase

shift of both reflected waves is 180o.

For such a coating on glass, at normal incidence, we need for constructive

interference

2 ncoat t = mλ, m = 0,1,2,...,

and for destructive interference we need

2 ncoat t = (m+½)λ, m = 0,1,2,....

For a film thickness equal to t = (1/4)λ/ncoat we get a net shift of ½ wavelength

between the wave reflected from the top and bottom of the film, resulting in

cancellation. For a non-reflective coatings the minimum film

thickness required is (1/4)λ/ncoat. A coating with

thickness t = λ/4ncoat prevents the reflection of most of the light with a

wavelength λ close to λ = 4ncoatt. The coating does not reflect a

specific range of wavelengths. Often that range is chosen to be in the

yellow-green region of the spectrum, where the eye is most sensitive. Lenses

coated for the yellow-green region reflect in the blue and red regions, giving

the surface a familiar purple color.

When sunlight reflects from a thin film of soapy water, the film appears multicolored, in part because destructive interference removes different wavelengths from the light reflected at different places, depending on the thickness of the film. As the film becomes thinner and thinner, it looks darker and darker in reflected light, appearing black just before it breaks. The blackness means that destructive interference removes all wavelengths from the reflected light when the film is very thin. Explain.

Solution:

A thin film of a material is floating on water (n = 1.33). When the material has a refractive index of n = 1.20, the film looks bright in reflected light as its thickness approaches zero. But when the material has a refractive index of n = 1.45, the film looks black in reflected light as the thickness approaches zero. Explain these observations in terms of constructive and destructive interference and the phase changes that occur when light waves undergo reflection.

Solution:

The colorful patterns that you see when light reflects

off a compact disk are produced by thin film interference.

The colorful patterns that you see when light reflects

off a compact disk are produced by thin film interference.

A compact disc is made of a polycarbonate wafer which is coated with a metallic film, usually an aluminum alloy. The aluminum film is then covered by a plastic polycarbonate coating. The coatings are less than 100 nm thick and each coating partially reflects and partially transmits incident light. Light rays reflected from different coating boundaries interfere with each other to produce the colorful patterns. The reflectance of the CD is not uniform, because CD disk contains a long string of pits written helically on the disk. These pits encode the information stored on the CD.

Thin film interference is used in industry as a non-contact, non-destructive way to measure film thicknesses.

Links: Thin film interference (part 1) Thin film interference (part 2) (Youtube)