The magnetic force on a moving charge

Moving electric charges produce magnetic fields.

Magnetic fields exert forces on other moving charges.

The force a magnetic field exerts on a charge q moving with velocity

v is called the magnetic

Lorentz force.

It is given by

Magnetic fields exert forces on other moving charges.

The force a magnetic field exerts on a charge q moving with velocity

v is called the magnetic

Lorentz force.

It is given by

F = qv × B.

(The

SI unit of B is Ns/(Cm) = T (Tesla))

The force F is perpendicular to the direction of the magnetic

field B.

It also is perpendicular to the direction of the velocity v.

F is perpendicular to the plane that contains both v and

B.

(Review the

vector or cross product!)

The magnitude of the Lorentz force F is F = qvB sinθ, where θ is

the smallest angle between the directions of the vectors v and

B.

If v and B are parallel or anti-parallel to each other,

then sinθ = 0 and F = 0. If v and

B are

perpendicular to each other, then sinθ = 1 and F has its maximum

possible magnitude F = qvB.

If a charge q is moving with uniform velocity

v parallel to

the direction of a uniform magnetic field B, it experiences no

force. It continues to move with uniform velocity v along a

straight line parallel to the field.

To find the direction of the

Lorentz force, use the

right-hand rule (Vector Product). Let the fingers of your

right hand point in the direction of v. Orient the palm of

your hand, so that as you curl your fingers, you can sweep them over to

point into the direction of B. Your thumb points in the

direction of the vector product v × B. If q is

positive then this is the direction of F. If q is negative,

your thumb points opposite to the direction of F.

To find the direction of the

Lorentz force, use the

right-hand rule (Vector Product). Let the fingers of your

right hand point in the direction of v. Orient the palm of

your hand, so that as you curl your fingers, you can sweep them over to

point into the direction of B. Your thumb points in the

direction of the vector product v × B. If q is

positive then this is the direction of F. If q is negative,

your thumb points opposite to the direction of F.

Problem:

On the surface of a pulsar, or neutron star, the magnetic field may be as

strong as 108 T. Consider the electron in a hydrogen atom on

the surface of the neutron star. The average distance between the electron

and the proton is 0.53*10-10 m. The average speed of the

electron is 2.2*106 m/s. Compare the magnitude of the electric force that the

electric field of the proton

exerts on the electron with the maximum magnitude of the magnetic force that the magnetic field of the

neutron star exerts on the electron. Is it reasonable to expect that the

hydrogen atom will be strongly deformed by the magnetic field?

Solution:

- Reasoning:

The electron in a hydrogen atom is at a distance r = 0.53*10-10

m from the proton.

The magnitude of the electric force acting on the electron is

equal to Fel = keqe2/r2.

The maximum magnitude of the magnetic force acting on the electron when its velocity

v is perpendicular to B is Fmag = qevB.

- Details of the calculation:

Fel = keqe2/r2

= 9*109*(1.6*10-19)2/(0.53*10-10)2

N = 8.2*10-8 N.

Fmag = qevB = 1.6*10-19*2.2*106*108

N = 3.5*10-5 N.

The maximum magnitude of the magnetic force on the electron is more than 1000 times stronger than

the magnitude of the electric force. We expect that hydrogen atoms will be strongly deformed

or destroyed on the surface of a neutron star.

Consider a charged particle with mass m and charge q

which at t = 0 has a velocity v perpendicular to

B.

This particle experiences a force with magnitude F = qvB perpendicular

to its velocity. A force perpendicular to the velocity results in

centripetal acceleration

a = F/m = v2/r. The

particle will move along a circular path. The radius of the circle

is

Consider a charged particle with mass m and charge q

which at t = 0 has a velocity v perpendicular to

B.

This particle experiences a force with magnitude F = qvB perpendicular

to its velocity. A force perpendicular to the velocity results in

centripetal acceleration

a = F/m = v2/r. The

particle will move along a circular path. The radius of the circle

is

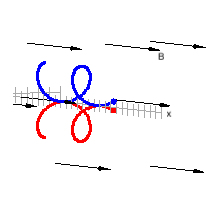

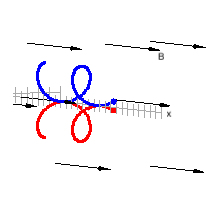

r = mv2/F = mv2/(qvB) =

mv/(qB),

and the circle lies in a plane perpendicular to

B. The

diagram on the right shows the paths followed by two charges, one

positive (red) and one negative (blue), in a magnetic field that points

into the page.

Since the magnetic force is perpendicular to the

velocity v = ∆r/∆t, it is, at any time, perpendicular to

the displacement ∆r. The work done by the magnetic force is

therefore zero, ∆W = F∙∆r = 0.

The magnetic force does no work.

The magnetic force changes

the direction of the velocity, but it does not change the speed or the

kinetic energy of the particle.

Assume a particle at t = 0 is moving

with a velocity v which has a component vperpendicular

perpendicular and a component vparallel parallel to

the magnetic field.

Assume a particle at t = 0 is moving

with a velocity v which has a component vperpendicular

perpendicular and a component vparallel parallel to

the magnetic field.

The path of the particle will be a spiral.

There is no acceleration parallel to B, but in the

plane perpendicular to B the centripetal acceleration

is a = qvperpendicularB/m, and the particle moves in a circle.

The superposition of these two motions results in a spiral path.

An interactive 3D animation of the motion of a charged particle in a uniform magnetic field.

Click here!

The magnetic force on a current-carrying wire

In a current carrying wire electrons move with an average velocity, called

the drift velocity vd. If the wire is placed into a

magnetic field B, a force will act on the wire.

Consider a straight section of wire of length L. The number of

moving electrons in this section is n-AL, where n-

is the electron density and A is the cross-sectional area of the wire. The

electrons move with the drift velocity vd. The force

F

on the section of wire is the sum of the forces on all the moving electrons,

F = -qn-ALvd × B

= jAL × B = IL × B.

Here we have used that -qn-vd = ρ-vd

= j, and that jA = I for a wire. Since I is not a vector and

we have to preserve the directional aspects of the vector product, we assign the

direction of the current density to L, which points in the

direction as j.

The force on a straight section of wire in a uniform field

B

is

F =

IL × B.

You can again use the right-hand rule to find the direction of the force.

Let the fingers of your right hand point in the direction of the current flow.

Orient the palm of your hand, so that as you curl your fingers, you can sweep

them over to point into the direction of B. Your thumb points in

the direction of the vector product F.

Problem:

A wire carries a steady current of 2.4 A. A

straight section of the wire is 0.75 m long and lies along the x-axis

within a uniform field B = 1.6 T in the z-direction. If the

current is in the positive x-direction, what is the magnetic force on

the section of wire.

A wire carries a steady current of 2.4 A. A

straight section of the wire is 0.75 m long and lies along the x-axis

within a uniform field B = 1.6 T in the z-direction. If the

current is in the positive x-direction, what is the magnetic force on

the section of wire.

Solution:

- Reasoning:

The force on the wire is given by F

= IL × B.

The direction of

L × B is the negative y-direction. Since L and B are perpendicular to each other, the magnitude F = ILB.

- Details of the calculation:

F = ILB

= (2.4 A)(0.75 m)(1.6 T) = 2.88 N.

The force on the section of wire is

F = -2.88 N j, in the

negative y-direction.

External link:

The Lorentz force

on a wire (Youtube)

Embedded Question 1

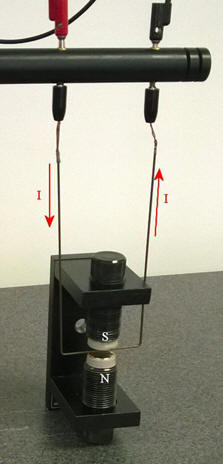

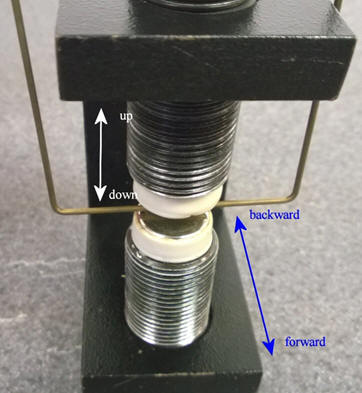

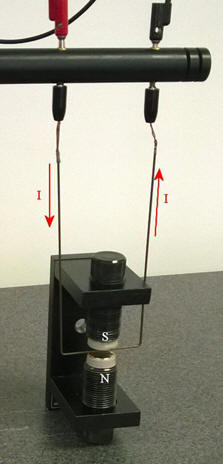

A demo: We pass a current through a wire a section of which passes

between the poles of two magnets, as shown below.

Make a prediction. When we connect the power supply, which way the wire will

move?

Discuss this with your fellow students in the discussion forum!

Review with them the Lorentz force and the right-hand rule.

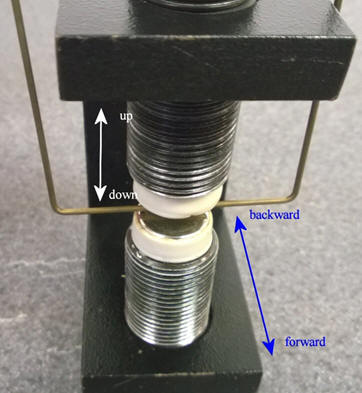

In this

video clip a hand crank generator is used to produce a voltage across

a thin rod which can move in a magnetic field produced by a set of magnets.

The north pole of the magnets points up.

In this

video clip a hand crank generator is used to produce a voltage across

a thin rod which can move in a magnetic field produced by a set of magnets.

The north pole of the magnets points up.

When

the crank is turned in the direction of the arrow shown, the red lead is

positive, and a current flows from the left to the right through the rod.

If the crank is turned the other way, a a current flows from the right to the

left through the rod.

When

the crank is turned in the direction of the arrow shown, the red lead is

positive, and a current flows from the left to the right through the rod.

If the crank is turned the other way, a a current flows from the right to the

left through the rod.

You can verify that the direction of the force F on the wire is the

direction of IL × B.

Problem:

Two parallel wires both carry current flowing in the same direction. Do

the wires attract or repel each other?

Solution:

- Reasoning:

Choose the coordinate system so that the currents flow in the z direction.

Let the second wire cross the y-axis at y = r.

The magnetic field B1 due to I1 in wire 1

encircles wire 1. it points in the negative x-direction at the

position of wire 2

The force on wire 2 is given by F12 = I2L2

× B1.

The direction of

L2 × B1 is the negative y-direction.

The force wire 1 exerts on wire 2 points in the negative y-direction,

towards wire 1.

Wire 1 attracts wire 2, By Newton's third law, wire 2 attracts wire 1.

Remember: Parallel wires carrying currents in the same direction

attract each other, parallel wires carrying currents in opposite directions

repel each other.

Please watch this video clip. It shows the effect described above.

External link:

Two wires (Youtube)

If you miss having regular lectures, consider this video lecture.

Lecture 11:

Magnetic field and Lorentz Force

Magnetic fields exert forces on other moving charges.

The force a magnetic field exerts on a charge q moving with velocity

v is called the magnetic

Lorentz force.

It is given by

Magnetic fields exert forces on other moving charges.

The force a magnetic field exerts on a charge q moving with velocity

v is called the magnetic

Lorentz force.

It is given by

To find the direction of the

Lorentz force, use the

right-hand rule (

To find the direction of the

Lorentz force, use the

right-hand rule ( Consider a charged particle with mass m and charge q

which at t = 0 has a velocity v perpendicular to

B.

This particle experiences a force with magnitude F = qvB perpendicular

to its velocity. A force perpendicular to the velocity results in

Consider a charged particle with mass m and charge q

which at t = 0 has a velocity v perpendicular to

B.

This particle experiences a force with magnitude F = qvB perpendicular

to its velocity. A force perpendicular to the velocity results in

Assume a particle at t = 0 is moving

with a velocity v which has a component vperpendicular

perpendicular and a component vparallel parallel to

the magnetic field.

Assume a particle at t = 0 is moving

with a velocity v which has a component vperpendicular

perpendicular and a component vparallel parallel to

the magnetic field.

A wire carries a steady current of 2.4 A. A

straight section of the wire is 0.75 m long and lies along the x-axis

within a uniform field B = 1.6 T in the z-direction. If the

current is in the positive x-direction, what is the magnetic force on

the section of wire.

A wire carries a steady current of 2.4 A. A

straight section of the wire is 0.75 m long and lies along the x-axis

within a uniform field B = 1.6 T in the z-direction. If the

current is in the positive x-direction, what is the magnetic force on

the section of wire.

In this

In this

When

the crank is turned in the direction of the arrow shown, the red lead is

positive, and a current flows from the left to the right through the rod.

If the crank is turned the other way, a a current flows from the right to the

left through the rod.

When

the crank is turned in the direction of the arrow shown, the red lead is

positive, and a current flows from the left to the right through the rod.

If the crank is turned the other way, a a current flows from the right to the

left through the rod.